The attribute that distinguishes the best teams from mediocre teams is trust. Lack of trust is often the unacknowledged root of business failure.

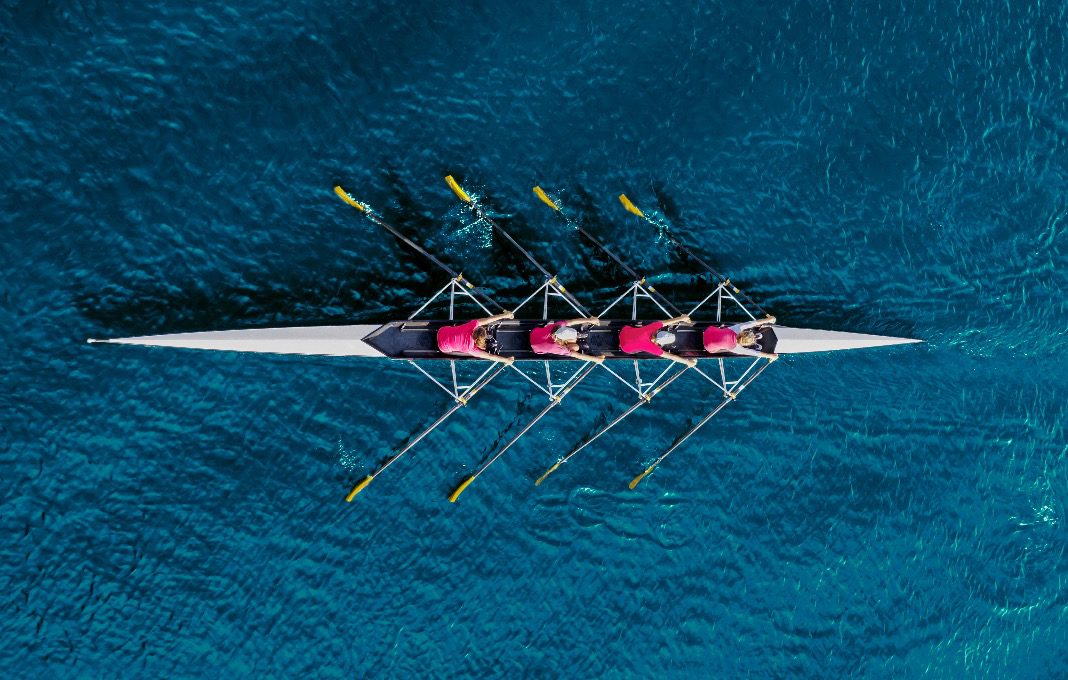

In business, team members must trust and work with cross-functional counterparts to synchronize plans. Businesses achieve their goals through teamwork, and teamwork is anchored in trust.

Using a team sports analogy, in ice hockey players have a decision to make when the puck is passed to them. One choice is to take the puck down the ice on their own to attempt to score a goal. They may have significant incentive to do so. They may be close to breaking a personal record or may believe that better scoring statistics will make them more marketable as a player. They also may not trust their teammates’ ability to score a goal. Another choice is to pass the puck to another player who is in a better position and can make a coordinated play.

How are players who always go it alone regarded by their teammates? Do the other players respect them? Will others pass the puck to them? How does this loner attitude impact the team’s win-loss record?

Consider this sports analogy in a business context. Collaborating with other business functions is often difficult for department leaders who may not trust other department teams to adhere to or execute the game plan. But they can’t go it alone and expect to win the game. They must understand the value of working collaboratively to carry out their commercial plan.

A shift in thinking occurs when department leaders focus on the betterment of the entire business. Sales and marketing leaders, for example, become more mature in their thinking about the demand plan. They consider the demand plan a request for product that they’re accountable for selling. The manufacturing organization is rarely an open bar, so to speak. Supply planners shouldn’t be forced to guess which of the demand mix, volume, or timing in the plan is going to come true, and which are hedges against possible poor performance from the manufacturing organization.

Similarly, the supply chain organization’s thinking shifts. They know the pitfalls of second-guessing the demand plan. The role of supply chain organization is to create a supply plan in response to the demand plan. This supply plan considers inventory, cost and service-level parameters that are deemed optimal.

Coordinating and synchronizing plans across functions enables coordinated responses to changes regarding both problems and opportunities. Doing so creates agility. When business leaders play their positions and trust their teammates to do what they say they’re going to do in their plans, something else happens. Responding to change becomes much simpler, and in some cases, effortless.

Take, for example, an organization where the sales, marketing and finance functions create their own separate forecasts. Imagine business leaders trying to decide whether or not to approve a customer promotion. The leaders will not understand whether the promotion is incremental to, or already included in, any of the different forecasts. They won’t understand which demand forecast the supply chain used to develop its production plan. It becomes very difficult to make the investment decision, let alone predict the outcome of the promotion.

Business leaders also would find it difficult to effectively respond to competitors’ moves. If competitors were to raise prices, introduce a new product, or exit a market, which forecast and information would be relied upon to assess the impact on the business? Which forecast would be used to understand the most effective actions to take in response? One forecast may have predicted the competitor’s moves. Another may not.

Situations like these arise when functional leaders resist sharing and aligning their functional plans. What happens when the sales and marketing teams fail to share their commercial plans with the finance or supply chain organizations? Those functions are forced to develop their own forecasts of demand. What happens when the manufacturing or supply chain team fails to share its supply plan? The sales, marketing and finance teams are forced to create their own projections of what will be available to sell.

The result of failing to share plans from a lack of trust is often a dangerous pattern of self-constraint. The sales team will hesitate to make commitments to customers when there’s uncertainty as to what can be delivered. The supply organization hesitates to commit to making product when there’s uncertainty as to whether the product orders will be received. The finance team will make their best estimates of sales revenue, margins and cash flow, all of which may not reflect reality.

The team should never be confused over which plan is being followed or that they can trust the information shared cross-functionally at face value.